- Build ships that can extract large volumes of nodules from the ocean floor.

- Indiginise or collaborate with global companies for extraction equipment.

- Develop in-house technology for extraction of metals from seabed nodules.

- Identify industries that can process these nodules and extract critical metals.

India joined the elite club of manned self-propelled comprising China, France, Japan, Russia, and the USA in October 2021 with the launch of Matsya 6000 to a depth of 500 meters. However, this is inadequate for seabed mining in sites allotted by the International Seabed Authority (ISA).

Most deposits of polymetallic nodules (PMN), polymetallic sulphides (PMS), and Cobalt-rich ferromanganese crusts (CFC) are found at depths between 4000 and 6000 meters in the Ocean. Under the Samudrayan mission, three personnel will be launched in a self-propelled human-occupied vessel (HOV) called the Matsya-6000 to six kilometres in 2026.

The PMNs, PMSs, CFCs nodules, and crusts strewn on the seabed have far higher concentrations of critical earth minerals than those found in continental ores. Commercialising deep seabed extractions can significantly boost India’s pursuit of blue economy and clean energy and hold promise for offsetting imports. Ministry of Mines has identified 30 minerals that are critical to our country.

Ironically, the OceanGate tragedy in June this year has brought the spotlight back on undersea exploration. It also raises questions about the need to undertake risky manned missions when remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) can perform all the functions.

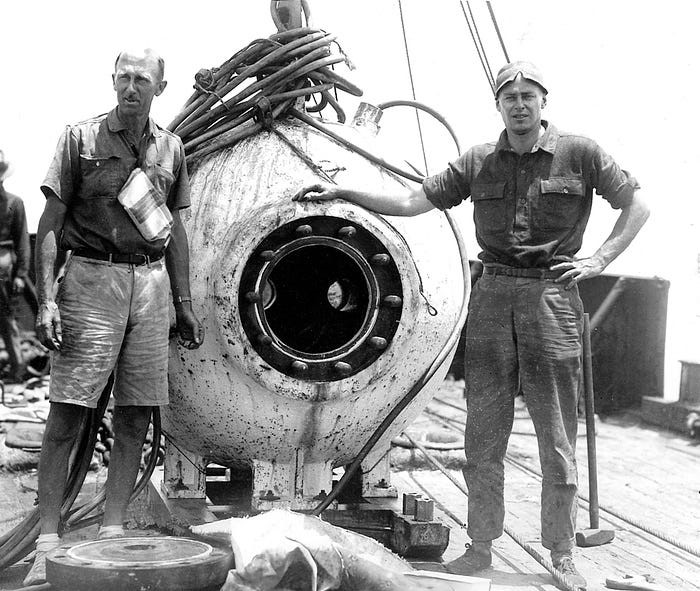

Manned submersibles aren’t risky if standards and certification procedures are followed. William Bebee and Otis Barton were the first to dive on 15 August 1934 to a depth of 923 meters in their vessel, Bathysphere. In 1960, Jacques Piccard and Don Walsh explored the Challenger Deep to a depth of 10,740 m in their vessel Trieste. There have been numerous crewed missions since in ocean submersibles. Deep sea exploration intrigues us because it conflates geology, biology, energy, chemistry, or simply mystery.

The Ocean is needlessly neglected. Less than five per cent of it has been explored. Even worse, we don’t care about what we don’t know. Cognizant of the immense hidden potential in the Ocean, the government of India approved the Deep Ocean Mission at a total budget of ₹4,077 crore ($480 mn) for five years. For the first phase, spanning three years from 2021 to 2024, a budget of ₹2,823.4 crore ($ 332 mn) has been earmarked.

Manned Submersible is critical for conforming to environmental norms, especially when commercial exploitation is outsourced to contractors. Seabed resources are a common preserve of humanity, and every nation is obligated to conform to the UNCLOS.

Matsya 6000 has been developed by the National Institute of Ocean Technology (NIOT), Chennai, an autonomous institute under the Ministry of Earth Science (MoES). Established in November 1993, NIOT has an enviable spectrum of mandates. Virtually all domains of ocean research is undertaken, including ocean-based renewable energies, ambient noise measurements, underwater communication, coastal surveillance, acoustic imaging, marine biotechnology, met-ocean and tsunami observation, beach restoration and shoreline management.

However, deepsea mining is the most cutting-edge of them all, as it provides solutions for Indian industry and helps them conflate the Prime Minister’s vision of “Blue Economy” and “Clean Energy”. But NIOT alone cannot achieve this vision. Critical metals will have to be extracted from PMNs and PMSs. Countries in possession of such niche technology do not normally share them. Hence, India will have to develop its own extraction technology and plants.

For minerals and materials research, a Common Research and Technology Development Hub (CRTDH) has been created in the CSIR-IMMT (Institute of Minerals & Materials Technology) at Bhubaneswar. CSIR-IMMT has procured a Transmission Electron Microscope (TEM) that will help characterise magnetic nanoparticles by evaluating the material structures, phase composition, and texture.

Once the extraction technologies are proven, private industries must create profitable ventures for the mass production of critical metals. Incidentally, a Udaipur-based company, Hindustan Zinc Limited, has already demonstrated the capacity to extract copper, nickel and cobalt from 500 kg nodules daily.

The estimated potential of polymetallic nodule resources is 380 million tonnes. It is expected to contain 4.7 million tons of nickel, 4.29 million tons of copper, 0.55 million tons of cobalt and 92.59 million tons of manganese. India renewed its PMN contract with the ISA for another five years in 2022 to tap the immense wealth lying on the seabed. A contract to explore PMSs from Central and South-West Indian Ridges (SWIR) was signed with the ISA in 2017 for 15 years.

Hence, launching India’s Matsya 6000 vehicle to a depth of six kilometres will be a significant milestone. However, several other challenges are ahead before India realises a viable seabed-based blue economy and clean energy. The way forward would be to:

- Build ships that can extract large volumes of nodules from the ocean floor.

- Indiginise or collaborate with global companies for extraction equipment.

- Develop in-house technology for extraction of metals from seabed nodules.

- Identify industries that can process these nodules and extract critical metals.

- Integrate a financially viable subsea mining value chain that will link ocean extraction, transportation, onshore production and markets.

- Expand exploration to other known areas in the Pacific, like the Northwest Pacific Ocean and Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ).

Dr Somen Banerjee

Commentary By

Dr Somen Banerjee is a Former Senior Research Fellow at Vivekanand International Foundation. He is currently associated with the MRC as a Senior Research Fellow.